“The loss of the nuts ended a way of life and brought economic hardship to many. ‘The blight was hard on people for chestnuts were used as money at the stores,’ Max Thomas said. Thomas was not alone in his belief that the death of chestnuts helped destroy a semi-subsistence economy and forced many mountain residents to find wage labor.” ~Ralph H. Lutts (2004)*

This is exactly what happened to the notable African American community at Coe Ridge, founded in 1866 in Cumberland, Kentucky. Here is an introduction to their unforgettable legacy.

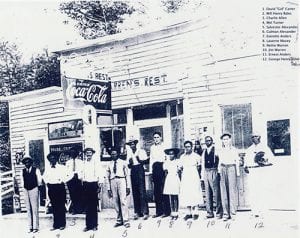

Residents of Coe Ridge in front of local business. Courtesy of Clio

Prior to blight, some chestnut orchards were natural stands of trees that, through the labor of individual farmers and their families, were culturally redefined as objects of agriculture. Given the efforts that farmers devoted to maintaining the orchards, it is reasonable to assume they tried to control access to them. If so, chestnut orchards were removed, to some extent, from the historic foraging commons. The Digital Library of the Commons defines “commons” as “a general term for shared resources in which each stakeholder has an equal interest.” Much of the unfenced rural landscape of the Appalachian region was a grazing and foraging commons.

According to folklorist William Lynwood Montell, the Coe Ridge Colony had “a large chestnut orchard,” which became contested ground: “Friction between the races was intensified by some of the white boys who made it a habit going to the ridge and freely partake of the abundant chestnut supply.” Their 300-400 acres of land filled with virgin timber provided wood to build homes while gathering wild chestnuts provided food and additional income. The residents who sold them for cash, resented the intrusion on their carefully maintained, private property. Unfortunately, this led to fighting and even deaths.

Enter chestnut blight: a colony that lasted almost 100 years, serving as a stronghold for blacks and displaced whites, saw their labor-intensive work dry up and foraging commons was no more. By the 1920s, residents resorted to moonshining and bootlegging to replace lost revenues from lumbering, farming and chestnutting. This economic suffering and surmounting legal pressure caused a sizable outmigration for industrial jobs in Ohio, Virginia, Pennsylvania, Virginia, and Illinois.

By 1958, the once raw, primitive ridge land that Ezekiel Coe purchased after gaining his freedom, founding the Coe Ridge Colony with his reunited family after being separated during slavery, was abandoned. Left in its wake are the Coe Ridge Cemetery, numerous folk legends, and lost reminders of slavery and emancipation.

Continue reading about how chestnut blight closed the foraging commons…

*Ralph H. Lutts, “Like Manna from God: The American Chestnut Trade in Southwestern Virginia,”

Environmental History, Vol. 9, No. 3 (Jul., 2004), pp. 497-525 (29 pages), DOI: 10.2307/3985770