American Chestnut History

History of the American Chestnut Tree

The history of The American chestnut and its relationship with humans is a tale of bounty, tragedy, and ultimately, of hope and redemption. The American Chestnut Foundation’s goal is to develop a blight-resistant American chestnut tree and to restore it to its native range across the eastern United States.

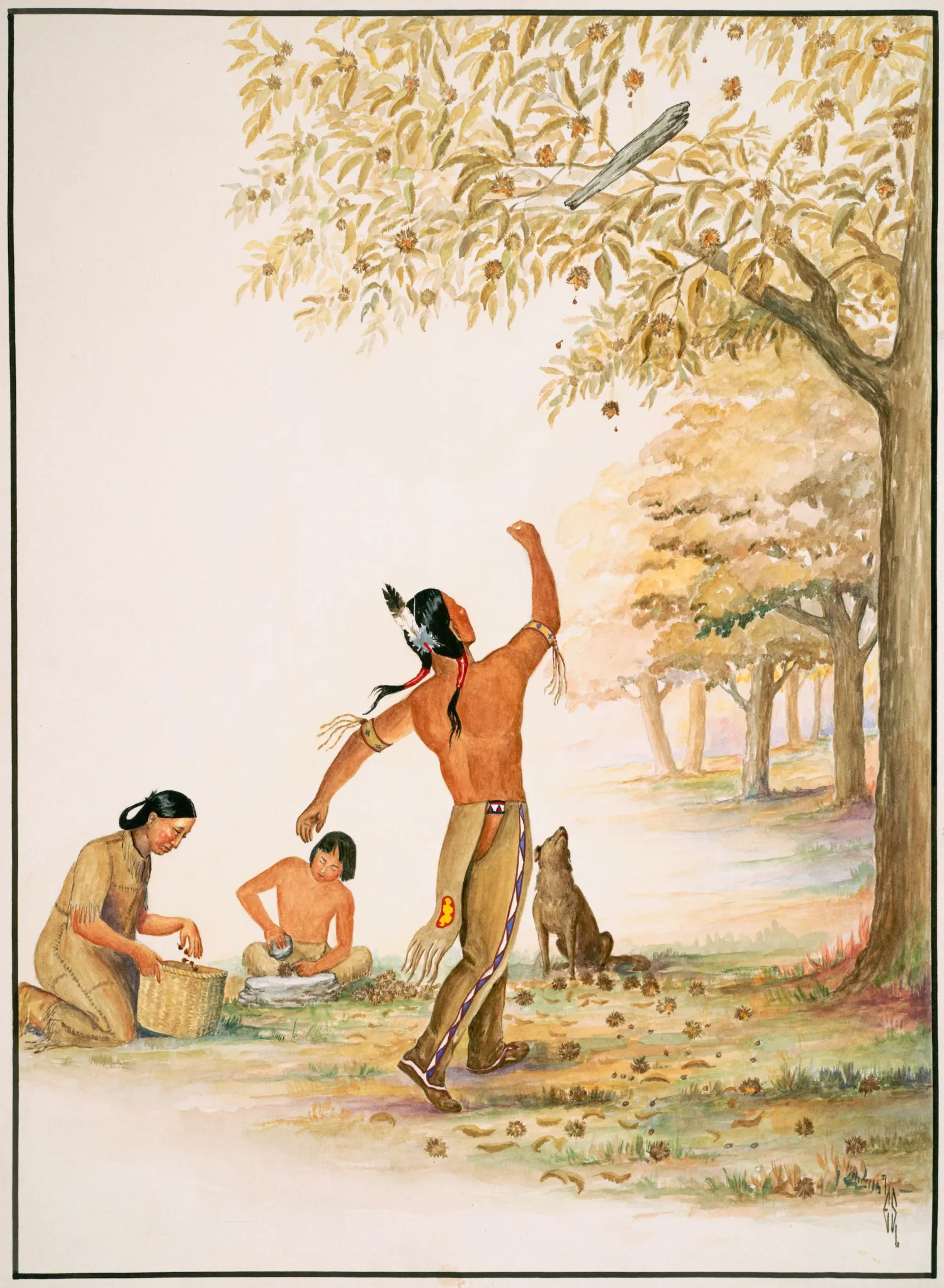

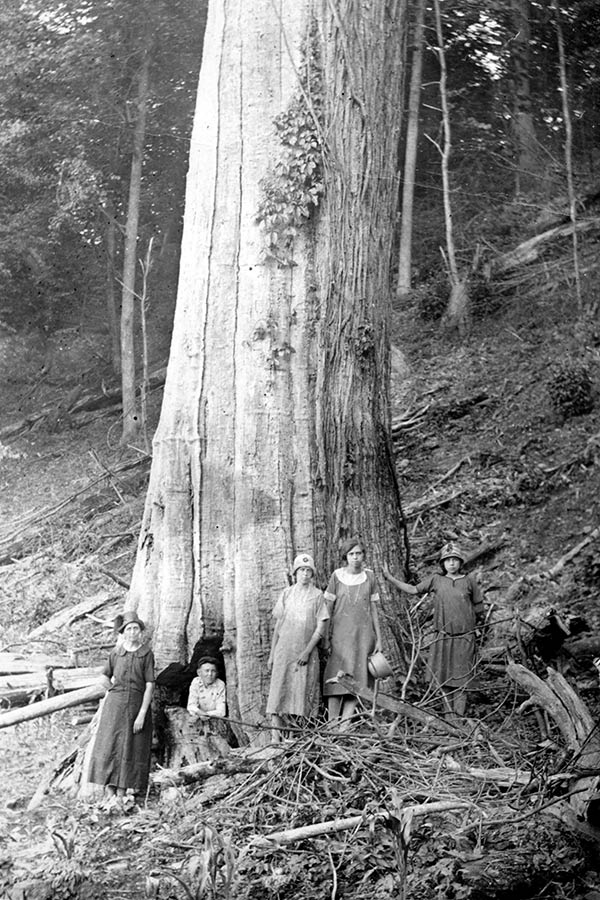

The American chestnut, Castanea dentata, once dominated portions of the eastern US forests. (View the American chestnut range map.) Numbering nearly four billion, the tree was among the largest, tallest, and fastest-growing in these forests. For thousands of years, the original inhabitants of the Appalachians coexisted with the American chestnut. (Read Indigenous Words for Chestnut.) The nuts provided an abundant food source, and Indigenous Peoples responded in kind by managing the landscape to improve habitat for chestnuts. Humans benefitted not only from the chestnuts themselves, but from the immense opportunities it created for wildlife.

Chestnuts are dense with calories, rich in vitamin C and antioxidants, and the leaves contain higher levels of essential plant nutrients than other local tree species. This made the chestnut beneficial not only for the humans of an ecosystem, but for every level of the food chain. Chestnut leaves were favorites of detritivore insects who, by breaking them down, enriched the forest floor with nutrients. Insects feeding on chestnut leaves were then eaten by fish or birds, and other larger animals would feed directly on the chestnut mast like squirrels, deer, bear, and turkeys.

Gathering Chestnuts, painting by Ernest Smith, with permission from the Rochester Museum and Science Center.

Jim and Caroline Walker Shelton’s family standing by a large American chestnut tree below Tremont Falls, Great Smoky Mountains National Park, circa 1920

As European settlers arrived and displaced native peoples, they learned that chestnut wood was rot-resistant, straight-grained, and suitable for furniture, fencing, and building materials. It was preferred for log cabin foundations, fence posts, flooring, and caskets. Later, railroad ties and both telephone and telegraph poles were made from chestnut, many of which are still in use today.

The American chestnut tree was a significant contributor to rural agricultural economies. Hogs and cattle were fattened for market by silvopasturing them in chestnut-dominated forests. Nut-ripening and gathering nearly coincided with the holiday season, and late 19th century newspapers often featured articles about railroad cars overflowing with chestnuts to be sold fresh or roasted in major cities.

All of this began to change in the late 1800’s with the introduction of a deadly blight from Asia. In about 50 years, the pathogen Cryphonectria parasitica reduced the American chestnut from its invaluable role to a tree that now grows mostly as an early-successional-stage shrub. There has been no new chestnut lumber sold in the US for decades, and the bulk of the 20-millon-pound annual nut crop now comes from introduced European or Asian chestnut species, or from nuts imported from Italy or Turkey.

Click the play button on the video to see an animation of the rapid spread of chestnut blight in the United States.

Simultaneously, a fungus-like organism called Phytophthora cinnamomi, likely transported to North America a hundred years before the blight, was killing American chestnuts primarily in the southern part of the range. The disease it causes, called ink rot or Phytophthora root rot, kills the entire tree by killing the roots.

American chestnuts re-sprouting from roots

Despite its demise as a lumber and nut crop species, the American chestnut is not extinct. The blight cannot kill the underground root system as the pathogen is unable to compete with soil microorganisms. Stump sprouts grow vigorously in cutover or disturbed sites where there is plenty of sunlight, but inevitably succumb to the blight. This cycle of death and rebirth has kept the species alive, though it is considered functionally extinct.

The American Chestnut Foundation is working to develop a blight-resistant and Phytophthora-resistant American chestnut tree through scientific research and breeding, and to restore the tree to its native range in the eastern United States. You can support this mission by becoming a member and learning more about The American Chestnut Foundation.