“Music from the river once was a lullaby to the great town that doesn’t have ears to hear it much anymore. Sometimes a rainbow spans the olden home place of the Principal People. But it doesn’t speak the same happy tidings to the same happy tribe. Even the tall, smoky-looking mountains are silent. Too silent.” –T. Walter Middleton

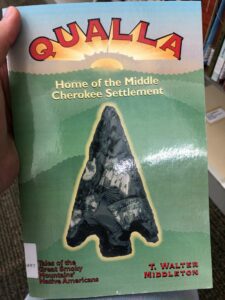

The cover of Qualla: Home of the Middle Cherokee Settlement by T. Walter Middleton

A few years ago, I spoke with Audrey Peterman, president and co-founder of Earthwise Productions, Inc., which focuses on connecting the public lands system and the American public. As an author of two books, she recommended I read Qualla: Home of the Middle Cherokee Settlement by saying, “It sets the stage with the chestnut forests of the Great Smokies.”

After a trip to the public library, I was pleasantly surprised to find within this book a Cherokee chestnut legend. To honor November as National Native American Heritage Month, below you can read that legend and take a historical journey.

Excerpt from Qualla: Home of the Middle Cherokee Settlement by T. Walter Middleton, pages 21-23

“If you talk to the right old-timers around Cherokee, you may find a few who will explain about one of the most delightful and welcome products that early inhabitants of these mountains had to sustain them. The Cherokee was just as dependent on and fought just as hard for the chestnut as he did the hunting ground. To the Cherokee, chestnuts were wilderness manna, food stamps and social security all out of the same burr [sic]. One of their most wonderful celebrations was at ‘Chestnut Time.’

Sometime during Kituhwa’s1 early existence, a beautiful legend was born about the chestnut and how the people obtained it. According to the story, because of several summer droughts in a row, a dreadful famine threatened the entire settlement, many people became hungry and sick. More than a few died. Wild creatures were thinned out because scarcely anything could be found for food. A medicine man had a dream that a certain mountain top high in the Smokies beckoned him to climb to its summit, and so he did. After a long wait there, he fell into a trance; he heard a voice instructing him, ‘Take this burr [sic] back to your people and plant its content. Trees will spring up there and, from their seed, hundred more will grow and feed all that are hungry.’ The medicine man did as he was bidden. Consequently, the mountains became full of chestnut trees. One-third to one-half of the trees in most wooded areas were chestnuts, making it readily available to mountain people and creatures.

The people learned how to do everything with a chestnut that could be done with it. They boiled it, roasted it, ate it raw. With its meat, they thickened soup and made their chestnut bread. Nothing was more versatile in season than chestnut. Only later did the Cherokees begin to cultivate corn in quantity. It matured earlier than chestnuts and was more easily stored over long periods. Corn earned its place in the Cherokee culture but no settlement could have survived the difficult periods of famine or disaster that periodically came upon it if the mountains hadn’t furnished chestnuts. Storage was not a problem since each household had root cellars anyway. Small rooms were dug into banks at times and pules of chestnuts were kept there.

Every traveler and hunter knew that there was survival ration covered with leaves most everywhere all winter long. What boy had not found the two small leaves peeping up in early spring and finger-dug the nut that produced them? Not enough credit is given, as we think of centuries gone by, to a simple nut, now almost extinct, that fed so many so long. It fed the Indian and it fed the animals that fed them.

There in the bottom where old Kituhwa was located, just up toward the foot of the hill, old folks used to say that the largest chestnut tree in the mountains once stood. In Kituhwa’s later years, the tree’s hollow base was used for a horse bar, and as many as six ponies were kept there. Some people were almost sure that the tree was one of the three original ones that were planted there so long ago. Of course, no one really knows. But the great tree and the great settlement are both gone now. Mr. Furgison, who owned and farmed the place for years, said that he plowed up many of the roots that were left of the great tree. Music from the river once was a lullaby to the great town that doesn’t have ears to hear it much anymore. Sometimes a rainbow spans the olden home place of the Principal People2. But it doesn’t speak the same happy tidings to the same happy tribe. Even the tall, smoky-looking mountains are silent. Too silent.”

1 Kituhwa or giduwa is an ancient Native American settlement near the upper Tuckasegee River, and is claimed by the Cherokee people as their original town, mother of the Principal People. An earthwork platform mound, built about 1000 CE, marks a ceremonial site here.

2 The Principal People, also known as the Anikituwah, and today known as the Cherokee. For thousands of years, prior to European contact, Cherokee people lived, worked, hunted, fished, and raised families on land that now makes up seven states in the southern United States.