Black History Month provides an important opportunity to honor the past while also recognizing how Black knowledge, leadership, and community continue to shape the present. From histories rooted in land and survival to modern platforms and outdoor spaces where connection and representation matter.

Throughout February, we will share a series of four stories that explore Black relationships to land, legacy, and community, looking at both historical foundations and contemporary expressions.

The Third Twenty: My Life of Forests and Farms

By Victor L. Harris

Publisher and Editor

Minority Landowner Magazine

February 17, 2026

My first introduction to forests was as a kid growing up in Georgia in a housing project that was surrounded by trees. That’s where I spent my childhood. Exploring the forests.

From there, I studied at Tuskegee University and North Carolina State University and learned the science and technical skills necessary to become a forester, earning my Bachelor of Science degree in forestry.

The First Twenty (1985-2005)

My professional career began as an area forester with the Virginia Department of Forestry. I was the first Black forester in the history of the agency. Within my territory, I worked with private landowners and led the agency’s programs and services which included forest management, fire management, insect and disease control, reforestation, and urban and community forestry.

I left during this period to establish Cierra Publishing Company and began publishing a regional magazine with an urban natural resource focus. Later, I suspended operations to join the North Carolina Division of Forest Resources, where I eventually advanced into the position of assistant state forester.

I’m fortunate to have begun my career with two well-respected state forestry agencies, both with great leadership and incredible employees dedicated to serving the forest landowners and citizens of their state. I include forest landowners and citizens, because when forest landowners are successful, all the citizens benefit.

It was a rewarding start to my career. However, I still had the itch to own my own company.

Victor Harris was a keynote speaker at TACF’s 2022 American Chestnut Symposium in Asheville, NC

The Second Twenty (2005-2025)

The 1920 Census of Agriculture reported 925,708 Black farmers in the US, 14.4% of all farmers. They managed 41,432,182 acres.

The 2022 Census of Agriculture reported 46,738 Black farmers, 1.2% of all farmers. They managed 5,323,654 acres.

During a period of 100 years, the number of Black farmers decreased by 94.9%. The number of acres these farmers managed decreased by 87.1%. There is no singular factor that led to such a steep decline; it is complex. If even in a small way, I wanted to join the effort to reverse the trend.

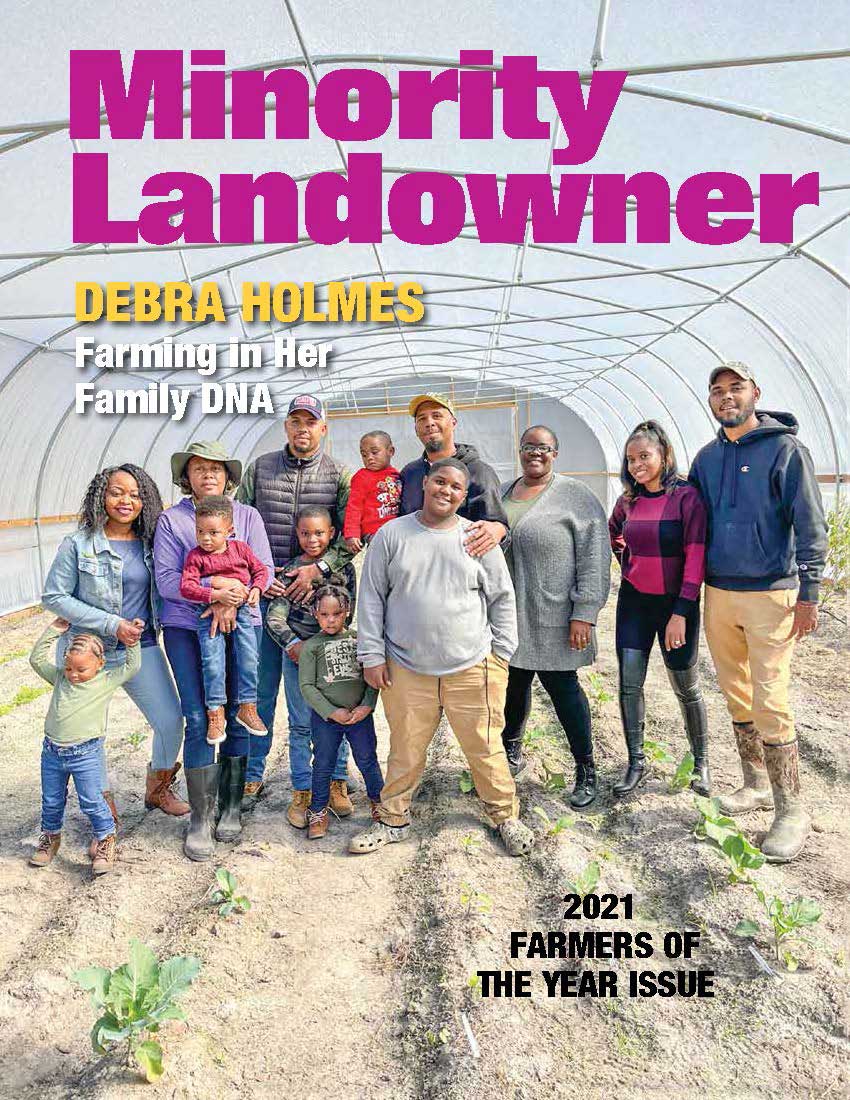

In 2005 we relaunched Cierra Publishing Company, and the first issue of Minority Landowner Magazine was published in 2006. The magazine has a national audience of farmers, ranchers, and forest landowners. Our goal is to provide information that can help them improve productivity, increase profitability, and maintain ownership of their land. We chronicle the challenges and successes they face and connect them with financial and technical resources that can help them find success. We’ve also designed and produced more than 100 webinars, workshops, field days, and national conferences.

Cover of Minority Landowner, 2021 Farmer of the Year Issue

The Third Twenty (2025-2045)

I refer to the next 20 years of my career in forestry and agriculture, The Third Twenty. This chapter has yet to be written. My dream is that Minority Landowner Magazine will continue working to build a path forward for Black farmers and other minority, limited-resource, and small farmers, ranchers, and forest landowners, much like the path being built to restore the functionally extinct American chestnut. That is, one in which a once bountiful population that contributed to the natural, economic, cultural, and social fabric of a proud community, can reestablish its place across the landscape.

As long as there are people willing to do the work to make it happen, there is hope.

Freedom Seekers and Chestnut

February 10, 2026

Enslaved Africans and African Americans who sought freedom by escaping slavery are called freedom seekers. One of the greatest challenges faced while heading north was the natural environment. The needs for food, shelter, and medicine were all critical components of the journey. While there was some assistance available throughout the journey from the Underground Railroad, survival and foraging skills were essential for freedom seekers navigating unfamiliar terrain.

Though it is hard to know exactly what was used by freedom seekers for food and medicine, historians have analyzed writings and texts of wild plants used for food and medicine to infer what may have supported these journeys. One example is the American chestnut. Not only were chestnuts plentiful in the Appalachian regions through which freedom seekers traveled, they also provided an important source of protein and nourishment. They could be eaten raw, boiled, or roasted. Medicinal remedies for children were made from roots boiled with milk, which produced an astringent agent. The benefits of chestnuts and other edible wild foods were crucial for freedom seekers during arduous journeys.

These findings demonstrate that the deep knowledge of plants and the natural environment played a significant role in the quest for freedom. Such understanding reflects the skills carried by Africans and African Americans and reinforces the idea that Black agency was central to the freedom seeker experience, demonstrating that these courageous individuals were not wholly reliant on white assistance to attain freedom.

Once freedom seekers reached their destinations, many of these foraged foods became part of the local culinary cultures, and medicinal traditions carried on as well. As a result, coastal areas of northern states, such as Pennsylvania, developed foodways distinct from those in western regions, reflecting the lasting influence of these survival practices.

For more information on the wild plants used by freedom seekers, read “Chapter 5: Living Off the Land” in From Slavery to Freedom.

Note: Michael Twitty, referenced in this chapter, was featured in TACF’s documentary Clear Day Thunder: Rescuing the American Chestnut. He is also the author of The Cooking Gene: A Journey Through African-American Culinary History in the Old South.

The Community of Coe Ridge, KY

February 4, 2026

School children and their teacher at the Coe Ridge Colony. Courtesy of Clio

“The loss of the nuts ended a way of life and brought economic hardship to many. ‘The blight was hard on people, for chestnuts were used as money at the stores,’ Max Thomas said. Thomas was not alone in his belief that the death of chestnuts helped destroy a semi‑subsistence economy and forced many mountain residents to find wage labor.”

~Ralph H. Lutts (2004), Like Manna From God: The American Chestnut Trade in Southwestern Virginia

This is exactly what happened to the notable African American community of Coe Ridge, founded in 1866 in Cumberland, Kentucky.

After the Civil War, Ezekiel Coe, a formerly enslaved man, together with his wife Patsy, founded what became known as the Coe Ridge Colony. In 1866, the couple purchased 300 acres of land from Ezekiel’s former enslaver, Jesse Coe. Over time, Coe Ridge became a refuge for African Americans, Native Americans, and white women who faced hardship and exclusion elsewhere.

The community grew into a rare example of Black land ownership and independence in post-emancipation Appalachia. Transforming overgrown, forested land into a functioning settlement required constant labor, collective effort, and a careful reliance on natural resources.

Among the most important of those resources were American chestnut trees. Prior to chestnut blight, these trees were a fundamental way of life for local communities like Coe Ridge. Many residents traded chestnuts for store credit, using them as a form of currency. The nuts also supplied food, while the trees themselves provided an excellent source of lumber—easy to cut against the grain and naturally resistant to rot, making them ideal for building shelter.

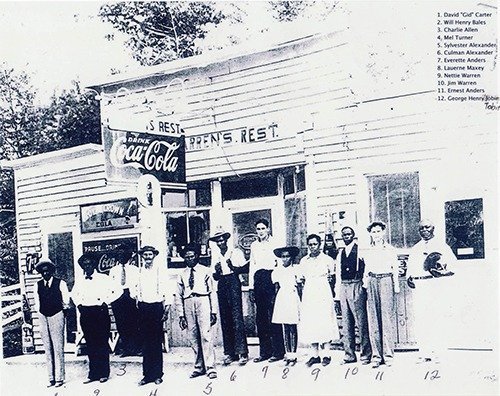

Residents of Coe Ridge in front of a local business. Courtesy of Clio

Although many chestnuts were gathered through foraging, the process was not always informal. Some residents maintained what were known as “chestnut orchards,” natural stands of trees that families carefully tended by clearing underbrush. By keeping the forest floor clean, farmers made it easier to locate and collect the fallen nuts.

In much of rural Appalachia, unfenced land functioned as a “foraging commons:” shared spaces where people gathered wild foods or grazed animals. The chestnut stands at Coe Ridge, however, were understood differently. Because residents invested so much labor into maintaining them, these orchards were considered private property, even if the surrounding landscape appeared open and unfenced.

According to folklorist William Lynwood Montell, the community at Coe Ridge reportedly had a “large chestnut orchard.” This orchard became a source of conflict with white neighbors who resented the presence and success of the Coe Ridge Colony. The land turned into contested ground, with each side claiming ownership, and therefore entitlement, to the profits the orchard produced. Ralph H. Lutts, Adjunct Professor of History at VA Tech, records that “friction between the races was intensified by some of the white boys who made it a habit to go to the ridge and freely partake of the abundant chestnut supply. The Negro boys and girls, who picked up the chestnuts and sold them for cash, resented the intrusion on their personal property. On one occasion, a fight over chestnuts broke out between the races.”

Residents who depended on chestnut sales deeply resented these intrusions into their carefully maintained property. According to Tim Coe, the disputes escalated into violence. “That’s what started all of the killing,” he recalled.

Then came chestnut blight. By the early twentieth century, the fungal disease had wiped out nearly all mature American chestnut trees. For Coe Ridge, the consequences were devastating. With the trees gone, chestnut harvesting ended, lumbering declined, farming income shrank, and the old foraging economy effectively disappeared. As Lutts observed, the loss of chestnuts helped destroy a semi‑subsistence economy and forced many people to seek wage labor elsewhere, with members of the community turning primarily to bootlegging and moonshining to survive.

Over time, families left the ridge in search of steady industrial work in Ohio, Pennsylvania, Virginia, and Illinois, following a broader Appalachian migration pattern. By 1958, the Coe Ridge Colony had become desolate, its once‑busy community abandoned. Today, only three houses, a cemetery, numerous folk legends, and lingering reminders of slavery and emancipation remain of the original 300 acres of Coe Ridge.